By Susan J. Palmer and Abdulmuqtedir Udun

Published on Bitter Winter on April 3, 2021

China’s record of discrimination against Uyghurs in soccer does not bode well for Beijing’s “Spirit of Olympism” amid preparations for the 2022 Olympic Games. When young Uyghur men get together to practice soccer, they become suspects engaged in “terrorist training.” Even intramural soccer matches between local Uyghur teams are ruthlessly suppressed as “illegal gatherings.” A prime example is the legendary “Golden Cup Soccer Tournament,” scheduled for August 1995 in the City Stadium of Ghulja, Xinjiang’s second largest city.

When sixteen Uyghur teams arrived, ready to compete, they found the tournament had been cancelled. Armed guards were posted at the stadium entrances. The playing field was flooded by firehoses and huge slabs of granite obstructed play. The four soccer managers had been arrested.

But the Golden Cup was far more than just another soccer event. For Ghulja’s Uyghur community it held a symbolic value. Two eyewitnesses to the event told us their story. A prominent Uyghur activist, Zubayra Shamseden of the Uyghur Human Rights Project based in Washington, D.C., referred us to her brother-in-law, Noor Polat Abdulla, who grew up playing soccer in Ghulja before his family emigrated to Australia when he was fourteen. Upon returning to Ghulja in 1994 to meet his future wife, he became involved in a religious revitalization movement sweeping through the Uyghur community.

Abdulla was appalled at how much Ghulja had changed. “There was widespread unemployment and sports were dead. Our youth were heavily involved in alcohol and drugs. On every street of Ghulja, I was told, there was a youth who was a drug addict.”

After meeting the charismatic Abduhelil Abdumijit, Abdulla joined his circle of friends—devout men in their twenties, who were intent on reviving the Meshrep, a traditional gathering for Uyghurs that featured speeches, songs, dance, and community suppers. Their plan was to use the Meshrep as a vehicle for drug rehabilitation that offered spiritual guidance to troubled youth. The plan succeeded. “Each street had its own Meshrep group,” recalls Abdulla. “I used to go to two or three Meshreps in one night and give talks. Abduhelil did the same.”

It was Abdulla’s suggestion to introduce soccer into the Meshrep gatherings. “My friends and I all bought soccer balls and we organized matches in Ghulja city. Every Meshrep had its own soccer team. We were out running in groups every morning in parks and getting fit. This was unusual, so the government was getting suspicious….”

The Meshreps served their purpose, Abdulla claims: “Drug addiction and alcoholism were decreasing. Within six months, two alcohol factories in Ghulja closed down. Liquor shops complained that now every day was like Ramadan!”

According to Mehmut, another Ghulja native who now lives in Canada, Ghulja’s drug problem in the ‘90s was much more serious than just “teens smoking weed.” Mehmut recalls sadly, “My brother, my sister, my cousins—they all had kids addicted to heroin. Eight died of an overdose, boys and girls in their teens or early twenties. The drug dealers first started coming to East Turkestan from the mainland around 1989, we felt the Chinese government was making no effort to stop them. Some of the parents begged the police to arrest the dealers, they think they were accepting bribes.”

In August 1995, the Meshrep leaders organized a major soccer tournament. Zubayra Shamseden, who was born in Ghulja, recalls: “My brother and brother-in-law were to play in this big tournament, the Golden Cup, the first ever in East Turkestan. We Uyghurs love soccer. Our young men are the best soccer players in the world! Everything was legal and all set up. Ghulja’s City Stadium was booked. Our young men were out running, kicking balls, getting in shape for the big match – and the Chinese authorities were getting worried. They saw this as terrorist training, as a threat to overthrow the government.”

On August 12, 1995, sixteen teams showed up at the stadium ready to play. But the police had blocked the stadiums’ entrances and placed slabs of granite on the muddy field, which was flooded by firehoses. Abdullah said, “The army parked tanks on every sports field in Ghulja for ‘military exercises and the radio was broadcasting news all day about how the Uyghur soccer tournament was an ‘illegal gathering.’”

The tournament’s organizers, Meshrep leaders Abduhelil, Ruzimemet and Abdugheni, tried to reason with the authorities, but they were promptly arrested. Furious at this treatment of their spiritual mentors, around 500 youth gathered on August 14, 1995, outside the Ghulja city government building and staged a peaceful demonstration, demanding the release of the three men.

Abdulla had returned to Australia by this time with his new bride, but he introduced us to his old friend, Abduwali, who had marched in this demonstration 25 years ago: “We were carrying banners and shouting slogans,” said Abduwali, who now lives in Australia. “Then the military arrived and pushed us into a narrow street, finally forcing us into this big courtyard that belonged to a restaurant. They dragged away Rehmettay, who was the leader of the demonstration. When we tried to protect him, they pointed guns at us. They placed snipers on the rooftop of the building across the street.”

Then the city mayor was brought in, a Uyghur named Polat who spoke to the demonstrators in their own language. Mayor Polat advised the youth to leave peacefully, promising there would be no reprisals. Later, Abduwali learned that Polat had secretly warned two demonstrators that machine guns were set up in the adjacent 12-story building, ready to fire had they refused to leave.

“Mayor Polat did what he could to help his Uyghur brothers,” Abduwali mused. “This soccer game was a major incident that happened before the [1997] Ghulja Massacre. It could easily have ended up as another massacre, except that Mayor Polat prevented it.”

The demonstrators agreed to leave, but it took over two hours because the military made everyone exit by a narrow gate. Abduwali recalls, “My friend noticed a video camera set up, filming everyone as they left the courtyard. We realized how dangerous this was, so we escaped the courtyard from the back, by climbing through a restaurant window. There were customers inside, so we sat down and ordered drinks, pretending we had been trapped there all morning. The police came and questioned all the customers. They believed us.”

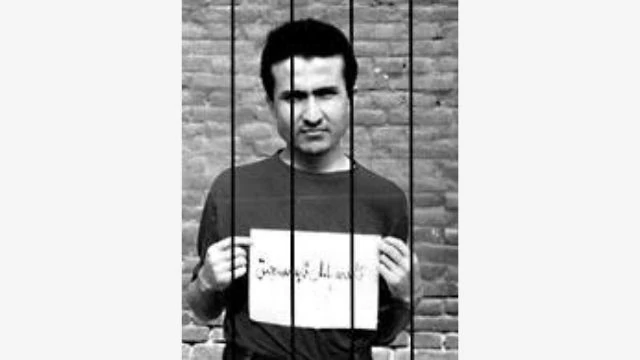

The next day, the police started tracking down the demonstrators identified on film. Hundreds of youth were arrested and given prison terms. The three Meshrep leaders disappeared into prison. Abduhelil went on a hunger strike and was taken to a hospital in 1996, from whence he escaped. While in hiding he continued to direct the Meshrep movement which had been outlawed following the cancelled soccer game. He appeared on February 5, 1997 openly leading a peaceful demonstration that quickly degenerated into the notorious “Ghulja Incident,” a brutal massacre commemorated every year by Uyghurs in the diaspora.

The pressure for a boycott or relocation of the 2022 Beijing Olympic Games has been mounting since last February, when Canada’s House of Commons voted overwhelmingly to recognize China’s treatment of its Uyghur minority population as a genocide. China’s treatment of Uyghursin soccer might appear a trivial issue in view of the human rights violations described in the international media. Since 2017 journalists have been reporting the arbitrary mass detentions of Uyghurs in the crowded “transformation through education camps” of Xinjiang. Reports of mass sterilizations and systematic rape of Uyghur women and forced labor camps have followed. But before deciding to sanction the Beijing Olympics, we should first consider the philosophy of “Olympism.”

The fundamental principles, first articulated by Pierre de Coubertin (1863 -1937), are outlined in the Olympic Charter. “Olympism” insists on non-discrimination; on every person’s right to practice sports regardless of race, color, sex, religion or social origin.

So, how does the spirit of Olympism apply to Uyghurs in soccer in China?

In October 2016, the authorities in Hebei province ordered Hengshui Power Football Club to expel nine of its Uyghur child trainees, citing “counterterrorism” concerns. This left the Uyghur children stranded, potentially with nowhere to go. Erfan Hezim, a promising Uyghur soccer player who was allowed to play on China’s national team, was arrested in February 2018 and incarcerated in a transformation through education camp until February 2019. Hezim had travelled with his soccer club to Spain and the UAE for professional training. He was the only player on the team for whom “foreign travel” was deemed a crime. He had to write a letter of thanks to the CCP before being allowed to return to professional soccer.

Beijing hotels have been advised to refuse accommodation to Uyghurs for fear of terrorist incidents. This means if the parents of Erfan Hezim or Muzepper Mirahmetjan—China’s only two Uyghurs in professional soccer—want to watch their sons compete in the capital, they will find themselves banned from Beijing hotels as suspected terrorists.

“They don’t want us to be heroes,” Abdulla explained. When asked about the next Olympics, he protested, “How can people go to Beijing and enjoy watching sports when they know that over a million people are suffering in concentration camps?”

Susan J. Palmer is an Affiliate Professor in the Religions and Cultures Department at Concordia University in Montreal. She is also directing the Children on Sectarian Religions and State Control project at McGill University, supported by the Social Sciences and the Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). She is the author of twelve books, notably The New Heretics of France (Oxford University Press, 2012).

Source: Bitter Winter

Copyright Center for Uyghur Studies - All Rights Reserved