Uyghur Figures – 10

Abdulaziz Jengizhan was born in the year 1906 in the County of Bugur, into a family renowned for its knowledge and erudition. His father, Ashur, was an accomplished religious scholar and a judge in the Sharia Court of Bugur. Abdulaziz received his primary education from his father and then proceeded to Kojak Province, where he continued his studies.

Upon seeking his father’s permission, he left his homeland to pursue his education at Al-Azhar University in Egypt. Following his father’s consent, he embarked on a journey from Bugur to Kashgar, enrolling in the prestigious Khanlig School, the Kashgar Royal Madrasa. In 1925, he arrived in India and studied at the Darul Uloom Deoband, one of the most renowned institutions in India, for a year and a half. During his time in India, he composed a Persian poem titled “Teeg Turkani,” in which he refuted the Qadiani sect that had emerged in India. This book was widely published in India in 1935 and circulated among Indian, Pakistani, and Afghan scholars.

There were rumors that he did not travel to India directly from Kashgar but rather from Nanjing, after pursuing political studies at Nanjing University. In 1926, he left India for Cairo, arriving in Egypt after a 21-day sea voyage. Due to his knowledge among his classmates and the passengers from India and Bengal on the ship, he led the prayers during this voyage. Demonstrating his geographical expertise, he initially prayed westward until reaching the middle of the Red Sea. As the ship approached the Arabian Sea, he shifted his orientation northward and gradually redirected it to the northeast.

However, the passengers on board were not pleased with these changes and blamed him for them. He explained to the congregation that the Qibla (the direction of prayer) was in Mecca, not in the west, and that Muslims in the west should face east, those in the south should face north, and those in the north should face south. However, the people did not heed his clarification; instead, they ridiculed him and refused to pray behind him. When the ship reached Jeddah, he prayed in the southeast direction. When the people witnessed these frequent changes, debates among them intensified and they abandoned him.

As the ship docked at the Suez Canal at noon, they entered the Suez Port Mosque to pray. After entering the mosque, they felt embarrassed because the Qibla was in the southeast direction. Subsequently, they apologized to him for their mistakes throughout the journey, honored and respected him, and began following his guidance. (Abdulaziz Jengizhan told this story to his students in 1946)

Upon his arrival in Cairo in 1927, he enrolled at Al-Azhar University for his higher education. In 1934, he graduated with expertise in jurisprudence (fiqh) and Islamic history. Later, he pursued further studies at Fuad I University (Cairo University) and eventually became a lecturer there. In 1939, he embarked on a journey to Mecca to fulfill the sacred duty of Hajj.

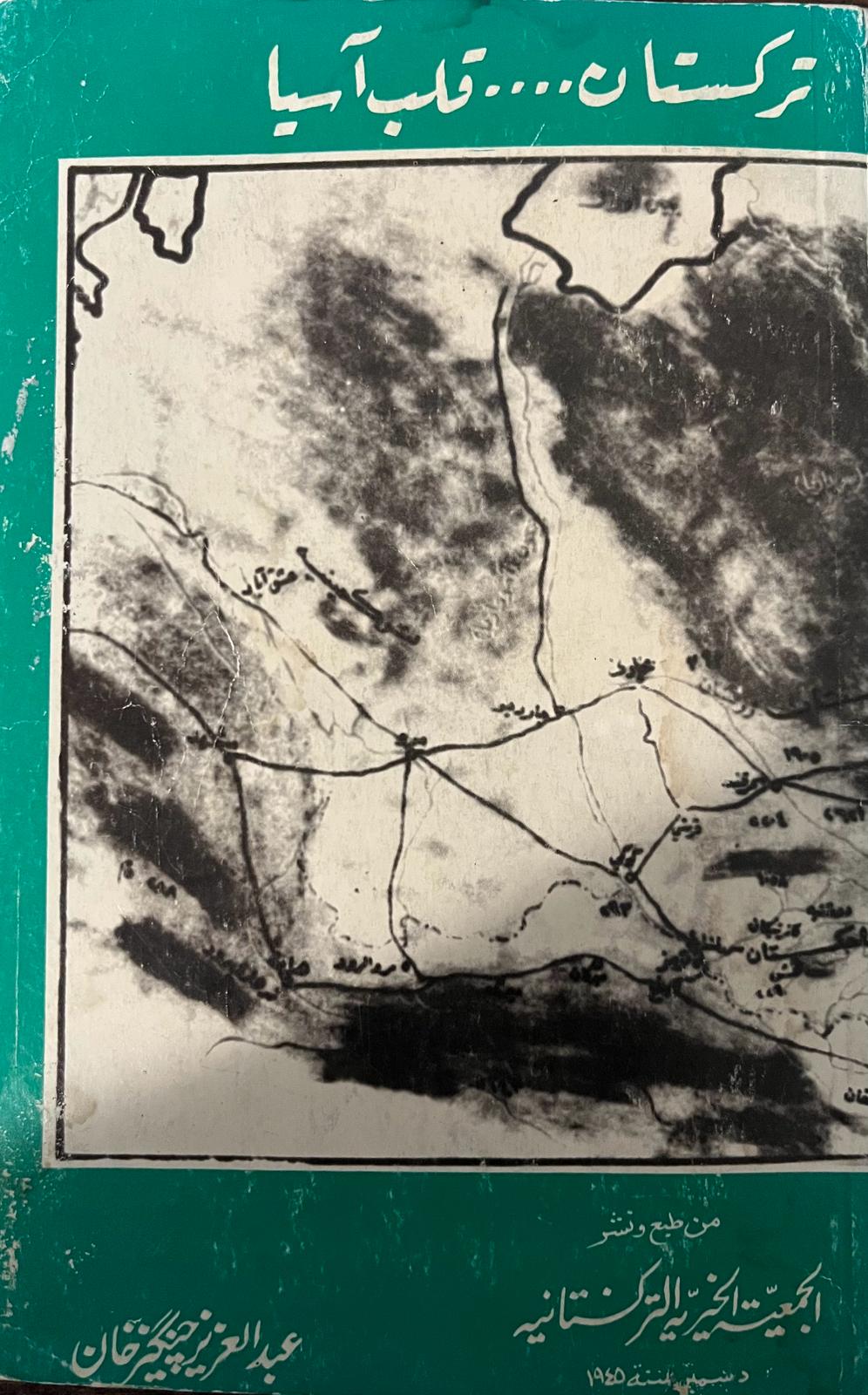

Jengizhan authored numerous literary works, encompassing both prose and poetry. Among his notable creations were “The Heart of Asia” and “The Voice of Conscience.” During his residence in Egypt, he forged a close friendship with the celebrated Egyptian poet Ali Mohammed Shaalan. Shaalan recounted that he had come across a manuscript authored by Jengizhan titled “Eternal Turkistan,” affirming that this work held great significance about the history of East Turkistan’s history.

Jengizhan’s literary contributions transcended boundaries, leaving an indelible mark on the cultural and historical tapestry of East Turkistan. His works, “The Heart of Asia” and “The Voice of Conscience,” stand as enduring testaments to his profound insights and literary prowess.

According to the autobiographical account penned by Yalqun Rozi and Sharif Hushtar in a Uyghur journal about Abdulaziz Jengizhan, he embarked on a remarkable journey in academia during his time at Al-Azhar University. He participated in the International Religious Scholars’ Debate, with a special permit granted by King Faruq of Egypt. In this prestigious event, he emerged victorious in the debate, earning praise from King Faruq, who exclaimed, “You are Jengizhan, conquering the realm of knowledge.” Henceforth, he became known as “Jengizhan.”

Furthermore, Abdulahad, his fellow classmate in Egypt, who later settled in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, recounted a different perspective during a meeting with Abdulcelil Turan in Istanbul in the summer of 1988. According to Abdulahad, Abdulaziz Jengizhan adopted this pseudonym himself.

Additionally, it is mentioned that Jengizhan engaged in scholarly discussions and debates with students from Tongzhou, who studied alongside him during his time in Egypt. He gained recognition for his articles and poetry during his studies in Egypt, further enhancing his reputation in the academic and literary circles.

During his days in Egypt, Jengizhan had a fortuitous encounter with Sheikh Tantawi Jawhari, the renowned scholar of exegesis, on one of the streets of Cairo. Sheukh Tantawi was deeply impressed by this young man who had journeyed from behind the Himalayan mountains, captivated not only by his scholarly prowess but also by his noble virtues, which he later extolled in his commentary.

Although Jengizhan received his education in religious schools, he was a man of profound spirituality and patriotism, a sentiment he eloquently articulated in the introduction to his book, “The Heart of Asia.” In these words, he emphasized the two fundamental obligations that every individual bears in this world: one is the religious duty, and the other is the duty to one’s homeland. He remarked, “In this worldly life, a person has obligations tied to his conscience, through which he attains happiness in both this world and the hereafter. Among the most crucial obligations in a person’s life are two: the religious duty and the duty to one’s homeland.”

In his unwavering commitment to these duties, he undertook the monumental task of translating the Quran into the Uyghur language to fulfill his religious obligations. Simultaneously, he authored the book “The Heart of Asia” to honor his obligations to his homeland. This book remains an indispensable source for scholars seeking to write the history of East Turkistan.

Reflecting upon the motivation behind his work in “The Heart of Asia,” he expressed, “Since my early days, I have felt a profound conviction compelling me to fulfill these two duties. I saw that serving one’s homeland was indeed a fulfillment of both of these obligations, measuring up to their rights at the same time.”

Jengizhan’s dedication to producing a book in the Arabic language on the history of Turkistan was driven by a profound sense of duty towards both religion and homeland. In his eyes, this endeavor was a means of pleasing Allah and serving his nation. He firmly believed that the history of the land and the history of Islam were inextricably linked. The history of the Turks cannot be comprehended independently, just as Islam cannot be fully understood without considering the history of the Turks. These two histories are intertwined, complementing one another like the soul and body, or like light and heat, inseparable and interdependent.

Therefore, he undertook this noble duty with utmost dedication, crafting a two-volume work that spans the entire history of Turkistan, from its earliest days to the present. He named this monumental work “Eternal Turkistan.” His intention was to present it to the public in its complete form, but due to paper shortages and prevailing circumstances, he had to delay its publication.

This book was first published in Cairo in 1945, and in 1986 in Pakistan for the second time, alongside his collection of poems titled “The Voice of Conscience,” thanks to the support of Abdul Sattar Maulvi, who resided in Saudi Arabia after the unfortunate events in East Turkistan. His poems in Arabic, written during his years of study and teaching in Egypt under the title “The Voice of Conscience,” were published in Cairo in 1944 and again in Pakistan in 1984. Furthermore, his book “Uyghur Syntax” (the science of syntax in the Uyghur language) was printed in Cairo in 1939. For those who seek comprehensive knowledge of Turkistan’s history, “Eternal Turkistan” is a source of abundance and healing.

Jengizhan’s enduring dedication to both his faith and his homeland is a testament to his deep sense of duty and the impact of his literary and scholarly contributions on the rich tapestry of Uyghur history and culture.

Moreover, in the course of his stay in Egypt, he had the honor of being associated with the Turkistan Association and the Turkistan Community in Egypt. They entrusted him with the task of producing a concise document on the history of Turkistan. He received this noble request with the utmost sincerity and responsiveness.

While Jengizhan was spending his days busy with his research and academic works in Egypt, letters from Turkistan began pouring in, urging him to return to his homeland. He confessed that his yearning for his homeland was no less than the homeland’s yearning for him. The call of his homeland beckoned him to illuminate it with his knowledge and contribute to the welfare of its people through the richness of its soil and skies.

Jengizhan returned to Urumchi in 1945, encouraged by his relatives Abdulhamid Mahdum and Ali Mahdum. Following his return from Egypt, he embarked on a journey to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, where he fulfilled the sacred duty of performing Hajj. During the pilgrimage, he met with Mahmud Muhiti, one of the leaders of the Islamic Republic of East Turkistan founded in 1933, and together they traveled to Japan. From Japan, he proceeded to Beijing and pursued studies at the University of Nanjing for a time.

Upon the unfortunate passing of Mahmud Muhiti, Jengizhan performed the funeral prayers and laid him to rest with his own hands. While there are reports suggesting that Jengizhan returned to Urumchi in January 1947 after working at the Egyptian embassy in Beijing, this does not align with his appointment to teach at the Khanlig School in Kashgar in March 1946, as previously mentioned.

Upon his return to Urumchi, he assumed the position of president of the Cultural Education Association and stood alongside Muhammad Amin Bughra and Isa Yusuf Alptekin in the struggle for the independence of East Turkistan and the freedom of the Uyghur people. He also contributed articles to the newspaper “Erik.” Furthermore, he delivered lectures on Islamic history at the Urumchi Teachers’ College.

In the spring of 1946, a committee was formed to review the activities of the Cultural Education Association throughout East Turkistan. They toured various regions, including Qumul, Yarkand, Kashgar, and Aqsu, and the visit spanned 63 days.

In September 1949, Jengizhan traveled abroad with Muhammad Amin Bughra, Isa Yusuf Alptekin, and others. While some of them managed to cross the borders, he was unable to do so and returned from the border. There are also opinions suggesting that he chose to remain in the homeland to continue the struggle.

Jengizhan was arrested in 1950 and executed by gunfire in Urumchi on February 25, 1952, along with a group of intellectuals like Ziya Samedi. This was due to his identity as an Uyghur nationalist who fought against the unjust rule of the Chinese Communist regime, which had inflicted immense suffering upon the people of East Turkistan.

Jengizhan showed a particular interest in elevating the religious and intellectual levels of Uyghur youth. In this regard, he delivered lectures on Islam and its history at the Urumchi Teachers’ College, led prayers with them, and provided religious and ethical instruction.

Jengizhan was at the forefront of scholars who emerged in East Turkistan to resist false doctrines and beliefs. He composed a poem in Persian titled “Tay Turkani,” addressing and refuting the claims of the Qadiani sect. Despite being of non-Arab ethnicity, he had a commendable command of the Arabic language, comparable to that of some Arab literati and poets. However, his special interest lay in his mother tongue.

He authored three books on this subject, but only one of them, “Uyghur Sarfi” (Uyghur Morphology), seeing publication due to various circumstances. In the introduction to this book, Jengizhan emphasized the importance of preserving one’s national culture and language for the continued existence of a nation. He argued that a people must have a strong understanding of their language to safeguard it against the encroachment of foreign languages.

Jengizhan’s focus extended beyond language alone. He dedicated his efforts to the history of the Uyghurs, emphasizing the need for deep study. To this end, he wrote a book on the geography of East Turkistan titled “Erkin Turkistan” (Free Turkistan) and another on the geography of Greater Turkistan titled “Ulugh Turkistan” (Great Turkistan). He also composed a collection of Uyghur poems titled “Guzel Turkistan” (Beautiful Turkistan), as well as works on Uyghur morphology, grammar, and “Islam in Turkistan.”

Among his notable works are “Turkistan Al-Khalida” (Eternal Turkistan), “Turkistan Qalb Asia” (The Heart of Turkistan), and “Sawt Al-Wijdan” (The Voice of Conscience). His book “Turkistan Qalb Asia” remains a primary source for Arabs and Uyghurs alike, helping to make Uyghur history known among Arab people.

Jengizhan also composed a Persian poem titled “Tayy Turkani,” in which he expressed his anger and aversion to false sects that presented themselves as Islamic. Regrettably, out of the 12 books authored by Jengizhan with his blood and sweat, only four were published, namely “Turkistan Qalb Asia,” “Sawt Al-Wijdan,” “Uyghur Sarfi,” and “Tayy Turkani.” His other works remain hidden, awaiting recognition in the literary world. These writings showcase his dedication to preserving Uyghur culture, language, and history. They serve as a testament to his commitment to the Uyghur people and their identity.

The life and legacy of Jengizhan remains a subject of intrigue and admiration, with multiple narratives shedding light on his intellectual journey and contributions to Uyghur literature and scholarship.

Written by: Abdulcelil Turan

Copyright Center for Uyghur Studies - All Rights Reserved